Industry Profile: MELANIE SIGGS

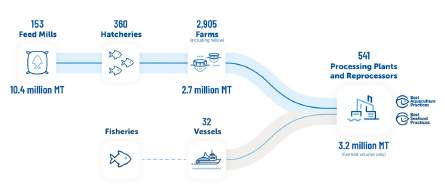

A: The Global Seafood Alliance (GSA) is an international nongovernmental, nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing responsible seafood practices through education, advocacy and third-party assurances. It operates a suite of seafood standards managed transparently through both expert and open consultation. There are currently some 4 000 facilities that have been third-party certified to those standards, across 43 countries. Customers include hatcheries, farms, processing plants, feed mills and fishing vessels. These facilities demonstrate they are operating at best practice – there are large parts of the seafood industry willing to commit to responsible practices and lead by example; we need to continue to grow that family.

Retailers need to have a suite of tools to meet responsible sourcing policies that require not only food safety and environmental best practice, but help ensure those working in supply chains have safe, decent, meaningful job opportunities. Quality standards that demonstrate best practice are one of the cornerstones of those tools, a foundation piece, in a portfolio of initiatives which all work together. Where the logo of the standard is shown on packs at point of sale, the shopper can be sure that those producing and sourcing the seafood are focussed on best practice standards and have demonstrated operations in place that can meet those practices, when followed with diligence. It has been shown that preparing for certification often results in improvements at facilities – a little like we might all need to brush up on our skills and knowledge if we had to take our driving test again!

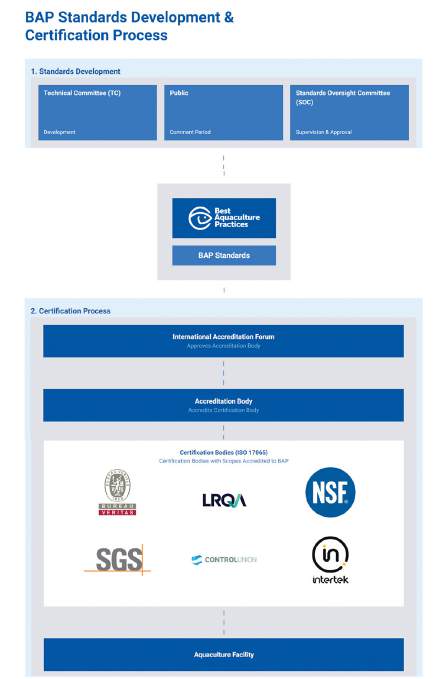

A: When we create a new standard or review or make alteration to an existing standard, we have a very strict process of governance, which involves an expert advisor consultation, a public consultation, and a review through the independent GSA Standards Oversight Committee comprised of members from academia, NGOs, and the industry. This can be a lengthy process but ensures any developments are created transparently, inclusively and with rigour before being incorporated. In some cases even after that process not everyone agrees with the outcome, but, provided they have participated, they can be sure our expert advisors and Standards Oversight Committee will have considered all input.

Auditors trained to audit GSA standards, from the accredited Certification Bodies (CBs), require all criteria to be met or for non-conformities to be rectified before certification is issued. However, there are instances, as have been highlighted, where the high standards have not been kept up between audits. There may be many reasons, that include changes in management or lack of training, Such instances have also highlighted new opportunities to improve the human rights criteria to better ensure people have the opportunity of decent, safe, empowering work in seafood supply chains. GSA is currently working with stakeholders from retailers to producers, including CBs and NGOs, to identify what changes can be made. It may be that a suite of tools of which quality, collaboratively and transparently created standards will remain an important anchoring component, but that also includes actions such as workers welfare questionnaires and more spot checks, creating a more comprehensive portfolio of due diligence. Continuous improvement is something we should all be committed to working on together as we learn and act – learning and circumstances change through time.

Q: Apart from aquaculture, according to reports, GSA is increasingly focusing on the fishing sector; specifically, social responsibility and the protection of human rights at sea. What are the GSA’s efforts to engage and push for the implementation and monitoring of best practices in this regard? (including crew wellbeing initiatives such as worker-driven social responsibility and Wi-Fi connectivity, if relevant).

A: GSA began to look at fishing, as part of seafood supply chains, in 2018 when we noticed the lack of assurance for big parts of the chain, specifically crew welfare on board fishing vessels and specialist seafood processing assurance. After an inclusive and transparent process, guided by global conventions such as ILOc188, we launched the Responsible Fishing Vessel Standard (RFVS) in 2020 (revised 2022). We also went through a process to ensure SPS – the Seafood Processing Standard – was suitable for wild harvest fish as well as aquaculture. This was when we changed the name from Global Aquaculture Alliance to Global Seafood Alliance, but the mission and governance remained the same.

As we developed RFVS and learned more about crew welfare on fishing vessels we led research on areas that lacked clarity, specifically Grievance Mechanisms and Worker Voice access. We published reports in 2021 and 2023. Something we noticed in the process of researching these areas was the need for crew on vessels to have robust connectivity to Wi-Fi at sea. Technology has historically prevented this, but accessibility is changing fast. Connectivity to personal phones and tablets at sea ensures crew can stay in touch with friends and family, which may be important for well-being and retention. It also means they can have digital copies of their contracts, potentially receive welfare questionnaires, access training or, for example, be in touch with Grievance Mechanisms or Worker Voice services when needed. GSA published a report on this topic in April 2024. We are continuing to work with technical experts, NGOs and vessel owners to accelerate access to Wi-Fi for crew at sea as a requirement.

Q: The Iceland Ocean Cluster, which you are an Advisor to, is described as “an industrial cluster fostering collaboration, innovation and entrepreneurship in the blue economy”. Reportedly, the Cluster is building a “network of ocean clusters globally to strengthen ocean industries in coastal areas worldwide and increase awareness of the blue economy”. In concrete terms, could you explain what this means? What kind of global cooperation framework is likely to take shape and what do you envisage will be the main areas of collaboration? (e.g. how many clusters are there so far; what are the processing and market benefits to companies of belonging to clusters; what are some of the projects that the existing clusters are working on, e.g. 100% Fish; and how will the global clusters work with each other?)

A: I’m proud to work with the Iceland Ocean Cluster who have led the narrative and awareness of full utilisation of seafood and how the cluster model can be a force for good in helping realise that.

Cluster models are not new, but within the blue economy context are rapidly growing. Each ultimately has its own unique model, but the principles of a shared vision and safe collaboration for mutual socio-economic benefit are common to all. Interestingly other models such as coalitions or alliances are often created to address challenges while cluster models tend to be used to create opportunity.

In Iceland the cluster is a privately-held SME model that centres on a dedicated building housing blue economy businesses and with a special focus on 100% Fish start ups and entrepreneurs. This model has, over the past decade, enabled the increase in value of the cod fishery from USD12 per fish to almost USD 5 000 per fish where the skins are now worth more than the fillets.

I was fortunate to work on the development of one of the newest blue clusters, the Namibia Ocean Cluster. The Namibia Ocean Cluster is a non-profit model with members of the hake fishery as Founder Members, all agreeing to the Mission around maximising socio-economic value through maximising utilisation and a financial contribution to fund a Secretariat, and other stakeholders such as NGOs and academics as Associate Members contributing expertise. The benefit is economies of scale and what they can achieve by working together in a safe, facilitated pre-competitive space.

Within this family of ocean clusters there are now cluster models either established or in development in, Pacific Islands, the UK, the USA, Europe and Africa. In this model, these sister clusters are able to support one another organically, learn from each other and benefit from a shared paradigm visibility.

Q: Moving on to a topic which you’ve been quoted as being passionate about – waste, or rather, “secondary yield”, as you have termed it. Examples abound of the innovative ways in which byproducts are being utilised by companies to make marketable products, including medical-quality graft material and leather items out of fish skin. At the small-scale level, with its attendant financial and knowledge constraints in most cases, are there any particularly innovative success stories that could serve as examples to emulate? (beyond fish cakes/sausages/crackers etc).

A: Thank you for noticing my desire that we stop saying waste and use the term ‘secondary yield’. The term secondary yield gives a more positive, targeted, purposeful frame to all that remains for capture and repurpose after the primary yield. It usually take some systemic change and mental shift to accommodate what we traditionally see as waste.

There are some compelling, fascinating papers in circulation in relation to the benefits of fish skin as a wound dressing. Not just cod, but other species and in particular tilapia. I have a big dream to find investors who will enable smaller start ups that create fish skin wound dressings on a regional level providing community and social benefit, but also increasing the value of the whole fish considerably.

Shells and heads from shrimp processing can be very valuable, both as high quality shrimp meal if attention is paid to the process – and shrimp meal can have terrific bioavailability, but also as the raw material for chitosan production. Chitosan has incredible properties. It’s used in the pharmaceutical industry to carry vaccines, for example. It is thought to reduce how much fat and cholesterol the body absorbs from foods. It also helps blood clot when applied to wounds. I’m sure we will see demand for chitosan raw materials grow – from shrimp, lobster, crabs – and maybe clusters can help fisheries and processors pool those resources.

Marine ingredients from secondary yield are undervalued, but there’s increasing evidence that when we treat residuals as a high value, quality, product not a waste, then the quality of the fishmeal is so much higher – resulting in good feed, more nutrients, better aquaculture, even improved disease prevention. It is time to ensure marine ingredients from residual material is valued and handled to optimise quality, nutrition and value, be that from wild capture fish or farmed.

We mustn’t overlook that eliminating waste in some small-scale fisheries is more about infrastructure. In many cases the whole fish is used, or would be used, but spoilage comes from, for example, a lack of cold storage or inadequate training on how to handle fish, post-harvest. There are many examples of community cold storage using solar power now, and FAO and local NGOs offer training, although both can be accelerated through political support. Other changes at a SSF level that can improve utilisation and socio-economic value include capturing residuals from potential wastage later in the chain by building in more processing at an early stage to capture a secondary yield. Community cold storage, training and processing might all be better enabled by creating local clusters to safely work together.

There’s a lot of work to do to understand the possibilities better, not least where we can create more franchise or cooperative style opportunities for good at regional or local levels, but we should hold on to that vision. I believe that maximising utilisation will become an expected part of best practice for fisheries management, aquaculture and processing in time.

Q: Ending on a personal viewpoint, would you say that the global seafood industry has been effective in explaining itself to dissenting environmental and consumer groups, in that it is working for the good of the planet and people? (e.g, documentaries such as Seaspiracy, plant-based “seafood”, environmental damage and contamination from farms).

A: It’s a depressing list of naysayers isn’t it. I truly believe that seafood, wild and farmed, provides some of the most nutritious, people and planet appropriate animal proteins possible as well as livelihoods, direct or associated, on so many levels. We can do it better yet, we can reduce footprints, improve aquafeeds further, ensure decent, safe, empowering work we are proud of, manage fisheries better, increase our understanding and data points, we can make sure use all we harvest; wild and farmed, we can attract more investment and research, we can demonstrate the incredible health benefits of seafood. AI and fast developing technology, as well as satellites, can resolve issues we haven’t even thought of yet, and enable us to, for example, manage fisheries in real time.

The business of blue foods and all they can do still excites and inspires me every day. I am very sad, and often a little irritated, when I see negative articles or documentaries. In part because there has to always be an element of truth albeit in a small minority, but also because of the damage it does to the significant community who are passionately committed to better blue food systems. Those investing, believing, researching, relying upon and committed to blue foods, and the non-targetted, but nonetheless impacted, parts of those ecosystems, like coral reefs, mega fauna, small communities, or air quality, that are a critical part of the future and which present immense opportunity for health and wealth for planet and people.

While there are still people and organisations who are providing content for the likes of Seaspiracy, we should be grateful to investigative journalists like Ian Urbina et al for their dedication to show us these pockets of atrocity that we must address, but it saddens me how much the public dissemination taints the whole industry.

We need political commitment, and I thank the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy for their leadership. The High Level Panel is an active group of 18 world leaders who have joined together to realise the mission of sustainably managing 100% of the ocean area under national jurisdictions. Political will is key, but we need good leadership at all levels to bravely drive, for example, research on disease, to enforce zero tolerance on illegal fishing, to address issues like flags of convenience, address plastic and other pollutants, to create enabling, real time and yet precautionary, resilient management, to lead optimum utilisation. We need to repurpose harmful subsidies, to ensure decent, safe, empowering work, create truly sustainable fisheries partnership agreements that benefit inshore fishers, we need more investment – mainstream, seed, development and blended and much more. We still have a lot to do, what we mustn’t do is get distracted and stop acting where we can now.

Fisheries and aquaculture, are not easy life choices. I thank all those who are committed to doing both well. To showing, by their leadership and example, what is possible. For your brave actions and voices engaged in national and global dialogues and helping build a strong, ever-adapting, global portfolio of best practice to show what blue food systems can positively do for people and planet.