BBNJ, RFMO’S AND MARKET: NEW CHALLENGES FOR

SUSTAINABLE TUNA FISHERIES

As countries like France rally for the Agreement’s activation by the UN Ocean Conference in June 2025, the urgency to bridge the existing divide in awareness and action amongst tuna RFMOs (t-RFMOs) and their stakeholders becomes evident. This lack of interest is remarkable, as well as surprising, because the new Agreement will require important adjustment of some of the policies at the RFMO level, such as a broadened scope of data collection in the scientific committees and a recalibration of policies at the RFMO level. This underlines the need for added resources and a fresh perspective on their global role in ocean management.

So, what is this treaty about, what does it stipulate and how will it affect sustainability governance in the tuna value chain?

The BBNJ Agreement, rooted in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), seeks to address the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction— areas previously left in a regulatory void. Its adoption is a testament to a collective realization: to achieve our global climate change and biodiversity conservation goals, a robust legal framework governing the high seas is indispensable. As a result, in 2004, the UN started the negotiations to address the conservation and sustainable use of marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ). After long and often complicated discussions, the BBNJ Agreement was finally agreed on 4 March 2023 by eighty-eight countries at the UN headquarters in New York. The treaty is now waiting for a minimum of sixty countries to ratify in order to move into the implementation phase.

Essential toolkit for biodiversity and climate change goals

It is a fundamental legal toolkit that is needed to accomplish the important international agreements on climate change, sustainable development goals and, most importantly, the so-called Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework to protect 30% of the planet’s land and oceans by 2030. This not only has to do with the enormous size of high seas (two-thirds of the ocean’s surface counting for about half of the Earth), but also with the vital role that healthy oceans play in global ecology and biodiversity, as well as climate change and CO2 storage. Without a framework for the governance of the high seas provided for in the BBNJ Agreement, all these other treaties will turn into paper tigers.

Part of the BBNJ’s toolkit will inevitably affect the way in which the management of sustainable fisheries will work in the future. The treaty, and more specifically, the Conference of the State Parties (CoP) that functions as the executive governing body, has the mandate to designate large parts of the high seas as a protected area with so called area-based management tools (ABMTs), including marine protected areas (MPAs)1. The difference between ABMTs and MPAs is a matter of their objectives. ABMTs range from single-sector tools that manage only one type of activity, to multi-sector tools that more comprehensively manage a wide breadth of activities. MPAs serve a specific long-term biological diversity conservation objective (as defined in the Convention of Biological Diversity) via multi-sector protections including for cumulative impacts from different human activities and climate change2.

To prevent harmful activities in protected areas, Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) will be conducted by the States with jurisdiction over these activities3. These EIAs screen new activities that may have irreversible impacts on the marine environment and that will need to be managed to avoid, mitigate, or manage potential significant adverse effects.

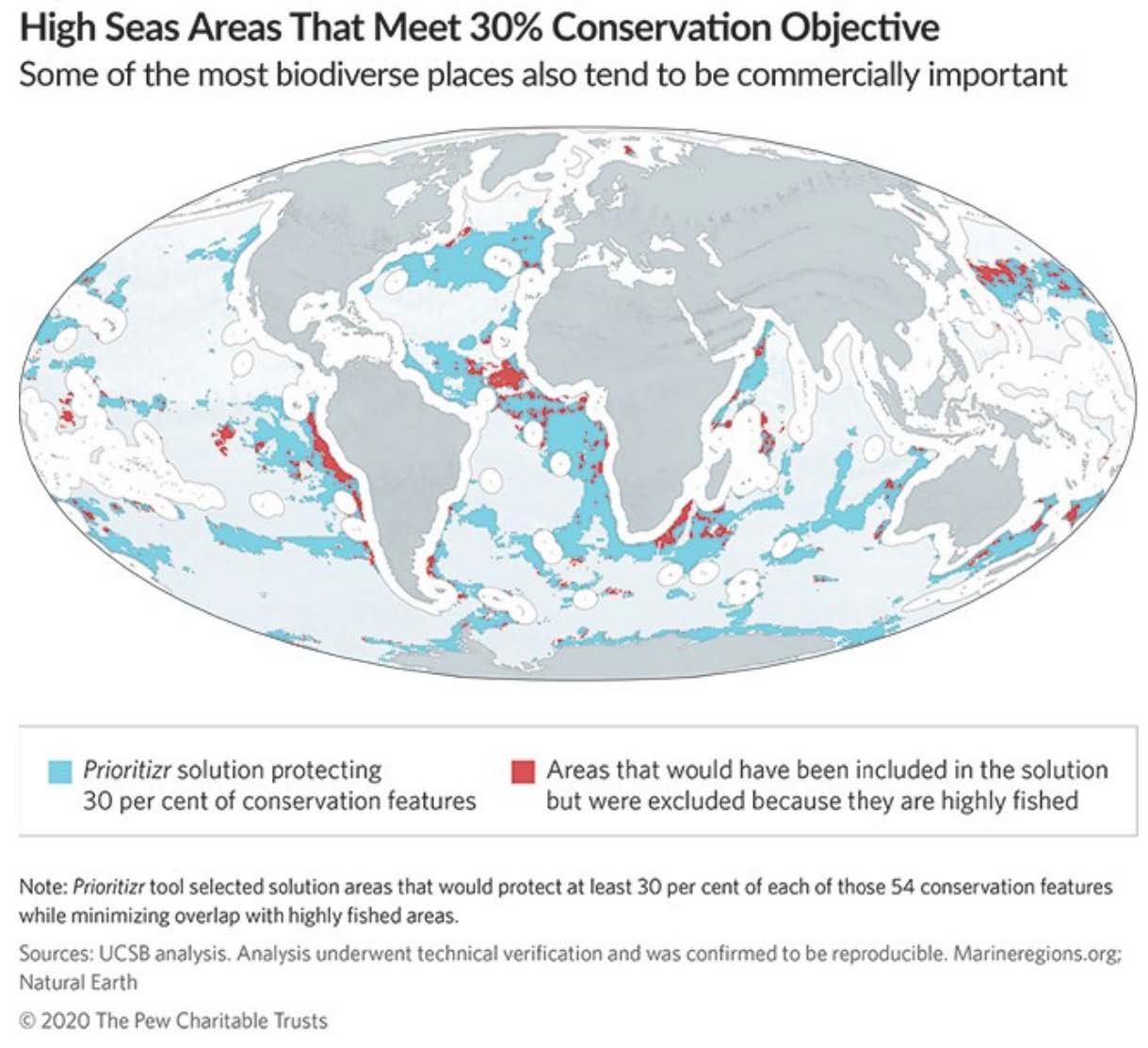

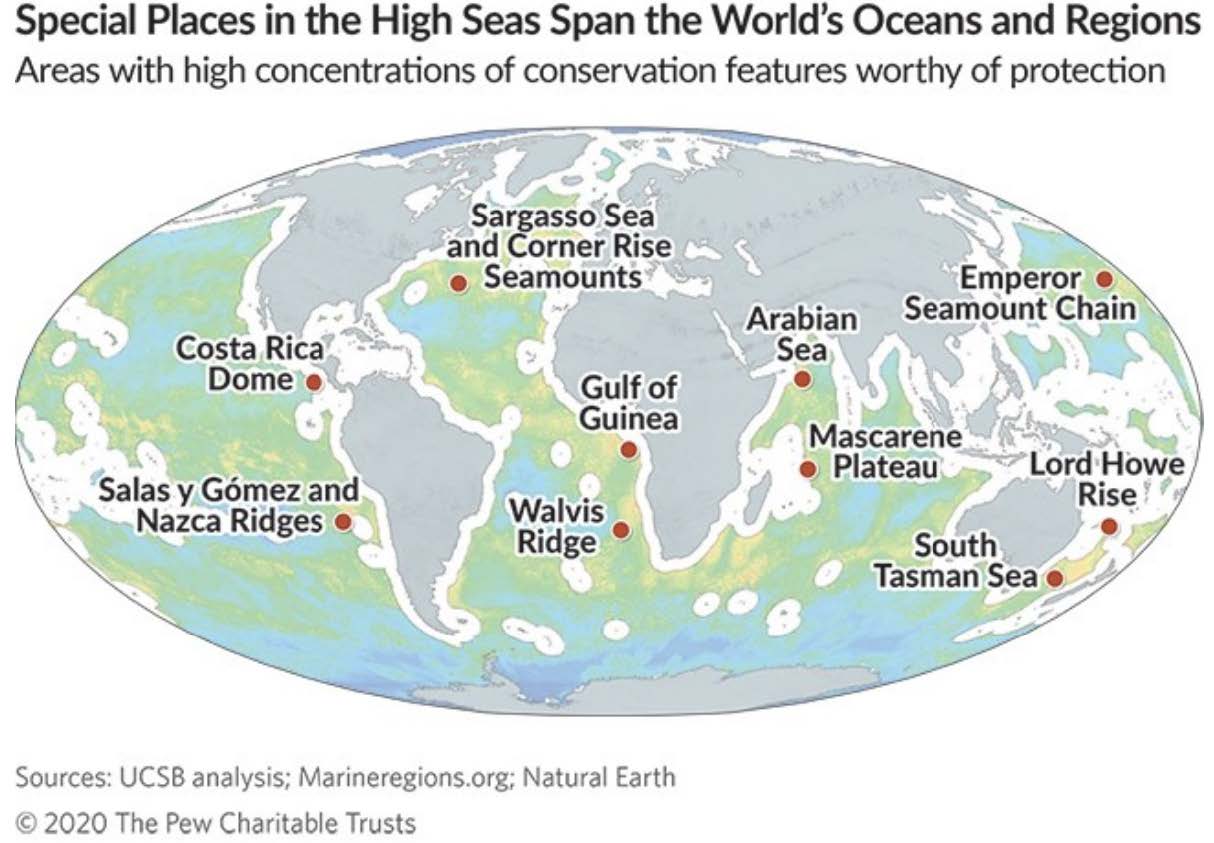

The convergence of BBNJ Agreement-protected areas and regions under RFMO jurisdiction highlights the critical intersection of global conservation efforts and regional fishery management. Researchers have mapped4 those areas that are considered to have priority regarding at least 30% of the targets for conservation of biodiversity. Part of those areas were excluded because they were highly fished. Also, a selection was mapped of ten sites with a high concentration of conservation features that might be considered as the first candidates for Marine Protected Areas under the BBNJ Agreement.

2) https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00908320.2024.2333893

3) https://www.highseasalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/FINAL-How-would-the-EIA-provisions-ofthe-BBNJ-Treaty-apply-in-practice-7.8.21.pdf

4) https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/03/a

The “not-undermining” principle

It was agreed that the treaty will be applied in a manner that “does not undermine relevant legal instruments and frameworks”{BBNJ Article 22(2)} of the existing regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs), the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) and the International Seabed Authority (ISA)7. The provisions of the BBNJ on genetic marine resources would also not be applied on the fisheries under RFMO competence.

But it was clear that the result did not take away the fear held by the industrial fisheries sector that the treaty could be used to overpower RFMOs and be counterproductive to fisheries management. “We ask the international community, relevant stakeholders, and environmental NGOs to focus on the challenges identified by the treaty, namely unregulated marine activities and unregulated marine areas”, Europêche president Javier Garat warned with obvious directness. “Wasting energy and effort in reinterpreting or distorting the BBNJ Agreement to try to overrule a robust fisheries management regime, would only serve as a deterrent and an excuse for its non-ratification”8.

Although the BBNJ will not directly impose procedures and management measures on RFMOs, this does not mean that its policy decisions; for example, regarding the establishment of an MPA, would have no consequences at RFMO level. As a general rule, the BBNJ provides for its State parties to cooperate with RFMOs and to promote the treaty’s objectives when participating in decision-making within them, including adopting relevant measures to support the MPAs {BBNJ Article 8(2)}. So, the primary responsibility lies with the States that are the parties to both the RFMO and the Agreement. These States are obliged to fulfil their obligations arising from both instruments. While the new governance framework respects the sovereignty of decision-making in both bodies, it remains to be seen how this crucial and controversial provision will work out in practice9.

6) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X22004195

7) https://www.highseasalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/HSA_Treaty_Factsheet_27June23.pdf

8) https://europeche.chil.me/post/europeche-welcomes-new-treaty-for-high-seas-432428

9) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0308597X23004852

Collaboration and consultation with RFMOs

With regard to the Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs), there is a provision that creates the possibility for impact assessment conducted by RFMOs to be used instead of an EIA procedure under BBNJ. A Party to the Agreement may decide to not undertake an EIA when provisions for managing planned activities are already addressed in the assessment of an RFMO (BBNJ Art. 29). An alternative for this assessment comprises RFMO regulations or standards that are designed to prevent, mitigate, or manage potential impacts below a threshold. When developing or updating standards or guidelines for the conduct of EIAs, the CoP is to develop mechanisms for its Scientific and Technical body to collaborate with the RFMO in order to regulate activities for protection {BBNJ, Art 29 (2)}. The overall obligation to perform an EIA is that Parties are to ensure that the potential impacts on the marine environment of planned activities under their authority or control, result in protection of the marine environment (BBNJ Art. 28).

To date, the great fears held by the industrial distant-water fleets have not materialized: the BBNJ as such is not “another institution” that can effectively “undermine” the existing relevant legal instruments and frameworks of the RFMOs or imply duplications in fishery management matters. Instead, the new governance framework interacts in a more complementary fashion: through procedures for collaboration and consultation, the RFMOs will participate in the decisions related to the BBNJ Agreement. The treaty’s approach—encouraging partnership and shared responsibility—ensures that fisheries management and biodiversity conservation go hand in hand. This, in turn, requires courageous and decisive involvement on the part of fisheries governance bodies and all the actors that make up the classic fisheries management framework10.

10) https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00908320.2024.2333893

11) https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2023/09/two-tools-can-help-makeecosystem-based-fisheries-management-a-global-reality

Market opportunities

Currently the claims refer to tuna in the can caught and managed in a way that guarantees healthy stock for future generations, but this is in many ways, a complex concept that is difficult to handle for the average consumer. Tuna caught respecting the role that healthy oceans play in global ecology, biodiversity and climate change can count on instant understanding and is therefore interesting as a marketing tool. The current fast development of new observer systems and tracking tools in the market chain make it possible that traders and retailers also can guarantee that the products in their cans effectively meet these new standards of biodiversity.

Conclusion