Article II 6/2024 - PERPETUATING INEQUITY IN SEAFOOD MARKETS: THE UNFAIR COST-BURDEN FACED BY SMALL-SCALE FISHERIES WHEN TRYING TO MEET MARKET REQUIREMENTS

Fifteen SIDS and eleven LDCs are located in the Asia-Pacific region, each facing specific social, economic and environmental vulnerabilities and constraints. For many SIDS, the majority of their natural resources come from the ocean, with the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of SIDS comprising, on average, 28 times the land mass of these countries. Their small population size, remoteness from international markets, high transportation costs, vulnerability to exogenous economic shocks and fragile land and marine ecosystems make SIDS particularly vulnerable to biodiversity loss and climate change because of their lack of economic alternatives2.

A sustainable ocean economy should put people at its centre - enabling human rights, facilitating the equitable distribution of ocean wealth and ensuring equal opportunities for all. Such equal access to resources will help ensure fair opportunities consistent with sustainable development. A sustainable ocean economy should further promote accountable and transparent business practices, including addressing labour rights abuses, tax evasion and corruption. It should also recognise the specific climate vulnerabilities and financing and capacity constraints of developing countries, particularly SIDS and LDCs3 4.

However, access to ocean resources and sectors is rarely equitably distributed. Many of their benefits are accumulated by a few, while most harms from development are borne by the most vulnerable in society. Inequity is a systemic feature of the current ocean economy. It is often embedded in existing political and economic systems, resulting from historical legacies and prevailing norms. Addressing existing inequalities, preventing the widening of ocean inequities, and promoting equity within and between countries, are integral to a sustainable ocean economy 2.

At the local scale, small-scale fishing communities, particularly indigenous, women and other minority subgroups, often have relatively limited political power, are less likely to be included in decision-making processes and suffer disproportionately from depleted ecosystems. Although small-scale fishers are often prioritised in fisheries management rhetoric, they mostly remain locked out of governance processes5.

2 United Nations Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States (UN-OHRLLS).

3 Österblom, H., C.C.C. Wabnitz, D. Tladi et al. (2020) Towards Ocean Equity. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at www.oceanpanel.org/how-distribute-benefitsocean-equitably.

4 Blasiak, R. (2019). Climate change vulnerability and ocean governance (Chapter 34). In: Predicting Future Oceans. Editor(s): Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M, Cheung, W.L. and Ota, Y. Elsevier.

5 Jentoft, S. & Chuenpagdee, R. (2015). In: Interactive Governance for Small-Scale Fisheries Vol. 13 (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

What type of future do we want?

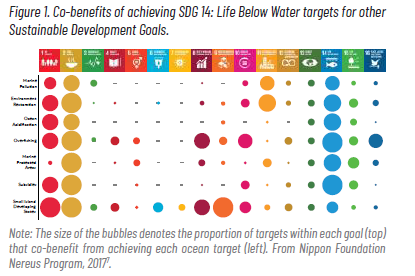

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is the plan of action to achieve sustainable development in its three dimensions – economic, social and environmental – in a balanced and integrated manner. It provides a vision for a world free of hunger and extreme poverty, with social justice and a healthy natural environment. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the Agenda provide the blueprint to achieve this vision. In fisheries, much emphasis is often placed on contributing to the targets under SDG14 ‘Life Below Water’. SDG14 targets also contribute to, and are required to achieve the other SDG targets in many ways. For example, a recent study showed that curtailing overfishing and ensuring equitable distribution of benefits (specifically highlighted through Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries) are expected to positively impact other SDG targets (Figure 1).

Key stakeholders in the sector recognise that environmental sustainability cannot be achieved if inequity is present; it is impossible to have a sustainable ocean economy without addressing the fact that 90%8 of fishers globally have inequitable access to ocean resources. The SDGs call for all businesses to contribute to their successful delivery, and collaborative partnerships are a key part of achieving a change that individual businesses cannot achieve alone. By taking a leadership approach and embedding SDG14b in their seafood procurement policies, global retailers would be aligned with other industry groups that embed the SDG agenda alongside their other activities, such as the Global Coffee Forum, World Banana Forum, Ethical Tea Partnership and Better Cotton Initiative. SDG14 cannot be achieved in isolation; it is widely recognised that the Global Goals are inherently interconnected. Action taken toward one Goal can support or hinder the achievement of others. While taking these interconnections into account is challenging, it is essential if we are to avoid our actions having negative unintended consequences and if we are to achieve holistic solutions9. All solutions must also be inclusive – at the core of the SDGs is the principle that ‘no one is left behind’10.

7. Nippon Foundation-Nereus Program. (2017) Oceans and Sustainable Development Goals: Cobenefit, Climate Change and Social Equity. Vancouver, p.28, www.nereusprogram.org

8. FAO, (2015) The Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines). FAO, Rome.

9. UN Global Compact. (2021) How business leadership can advance Goal 14 on Life Below Water.

10. Tulder, R. van (2018) Business & The Sustainable Development Goals: A Framework for Effective Corporate Involvement, Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Rotterdam.

What are non-tariff measures and trade barriers and how can they further drive inequity?

Compliance with private sustainability and certification standards remains an issue for small-scale fishers to overcome to access many international markets. Retailers in many developed countries increasingly set sustainability and social responsibility requirements when sourcing their products. While these programs have a role to play in sustainability, they tend to marginalise small-scale operators who do not have the requisite financial, technological or human resources to meet such requirements. The wide range of fisheries certification schemes poses further challenges for small-scale fisheries operators12.

The UN FAO Committee on Fisheries (COFI) is a global intergovernmental forum where major international fisheries and aquaculture problems and issues are examined and recommendations addressed to governments, regional fishery bodies, NGOs, fish workers, FAO, and the international community. The 19th session of COFI’s Sub-Committee on Fish Trade held in Bergen, Norway, in September 2023, advised that “certification standards are not always well-tailored to SSF and could act as non-tariff trade barriers. The Sub-Committee expressed support for the analysis of certification schemes for SSF and called for a judicious review of the FAO ecolabelling guidelines as part of efforts to ensure sustainable market access and trade for SSF, noting that concepts around sustainability have evolved since the FAO ecolabeling guidelines were adopted more than a decade ago”13.

New research published earlier this year also found that the MSC is failing to identify forced labour violations in the fisheries, which it certifies despite claims to the contrary. Data from 3 313 tuna vessels listed on MSC’s website found that 74% of MSC’s certified sustainable tuna was untraceable to vessel owners or fishing employers16. The authors argue that when consumers buy eco-labelled tuna, it would be reasonable for them to perceive that the MSC logo signifies that the product was made without crime and human rights abuse, especially where those assurances were made. The same is true for a supermarket buyer or a government perceiving that the tuna goods need no further human rights due diligence16.

12. COFI. (2022) Small-scale Fisheries and International Trade. 18th Session of the COFI Sub- Committee on Fish Trade. April 2022.

13. FAO. 2024. Committee on Fisheries: Report of the 19th Session of the Sub-Committee on Fish Trade, Bergen, Norway, 11–15 September 2023

14. Le Manach, F., Jacquet, J.L., Bailey, M., Jouanneau, C. & C. Nouvian. 2020. Small is beautiful, but large is certified: A comparison between fisheries the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) features in its promotional materials and MSC-certified fisheries. PLoS One. 2020 May 4;15(5).

15. Nyiawung, R.A., Raj, A. & P. Foley. 2021. Marine Stewardship Council sustainability certification in developing countries: Certifiability and beyond in Kerala, India and The Gambia, West Africa, Marine Policy, Vol 129.

16. Nakamura, K. (2024) Is tuna ecolabeling causing fishers more harm than good?. npj Ocean Sustain 3, 39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-024-00074-6

Many MSC-certified fisheries are recipients of these harmful capacityenhancing subsidies that are used for fuel tax breaks, the technology used in ‘the race for fish’, and the construction of new vessels. For example, fuel tax exemptions for the EU fishing industry to the tune of €759 million to over €1.5 billion are of special concern in light of the global climate and biodiversity crises. By exempting marine fuel from taxation, the EU is using public money to subsidise the burning of fossil fuels and incentivise pollution. This money can be seen as a huge support mechanism to mostly large, industrial, and often destructive, fishing fleets. In the process, low-impact and small-scale fishers who won’t reap the benefits from these subsidies are sidelined and pay the price in declining fish stocks and marine health, as well as increased vulnerability to worsening climate change18.

In Pacific tuna fisheries, the fleets of all distant-water fishing nations (DWFNs), many of which are part of MSC-certified fisheries, have benefited and continue to benefit from subsidies19. For instance, Chinese fleets are receiving significant subsidies that can lower operating costs and allow companies to profit where they otherwise would make a loss20. This can give those vessel operators a significant competitive advantage over Pacific Island Countries’ domestic fishing fleets, which may not be in receipt of such lucrative subsidies21. Fisheries subsidies also often enable foreign fleets to operate at sub-market rates, putting local fleets out of competition for their own fishery resources22. Joint-ventures, pseudo-joint-ventures and charter agreements allow DWFN fleets to take further advantage of developing coastal states in agreements that disproportionately benefit the foreign fishing powers23.

18 Our Fish. 2021. Climate Impacts & Fishing Industry Profits From EU Fuel Tax Subsidies.

19 Industrial Economics, Incorporated. 2023. Trade Flow Analysis of Pacific Tuna Fisheries Final Report. September 7, 2023.

20 World Bank Group (2017) Tuna fisheries. Pacific possible series, background paper no. 3 Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group.

21 Schuhbauer, A., Chuenpagdee, R. Cheung, W.L.W., Greer, K. & Sumaila, R. (2017). How subsidies affect the economic viability of small-scale fisheries, Marine Policy, Vol 82: 114-121.

22 Sumaila, R., Dyck, A. & Baske, A. (2014) Subsidies to tuna fisheries in the Western Central Pacific Ocean. Marine Policy. 43. 288–294.

Conclusion

One of the decisions from COFI’s 36th session held in Rome in July this year was to request “FAO’s assistance to address challenges in market access, fisheries statistics and cross-border trade, especially for SSF in the context of fish trade, including by updating the FAO ecolabeling guidelines to align with global instruments such as the Voluntary Guidelines for Small-scale Fisheries (VGSSF). Such an update of the Ecolabelling Guidelines, which were last revised in 2009, would provide an ideal opportunity to define sustainability in fisheries across the SDG targets and recognise the importance of climate change and social equity across seafood supply chains.

Global retailers who truly support sustainable development as envisioned under the SDGs, ‘where no one is left behind,’ should revisit their seafood procurement policies and ensure that they recognise the crucial role that small-scale fisheries play in achieving a better world. Seafood produced in industrial fisheries, propped up by harmful subsidies and relying on cheap, exploitative labour, cannot be called sustainable even if it is adorned with the familiar blue tick logo of the MSC!.

24 Roberts, C., Béné, C., Bennett, N. et al. (2024) Rethinking sustainability of marine fisheries for a fast-changing planet. npj Ocean Sustain 3, 41. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-024-00078-2