Article II 5/2024: SHOW ASIA ADOPTED NORWEGIAN SALMON

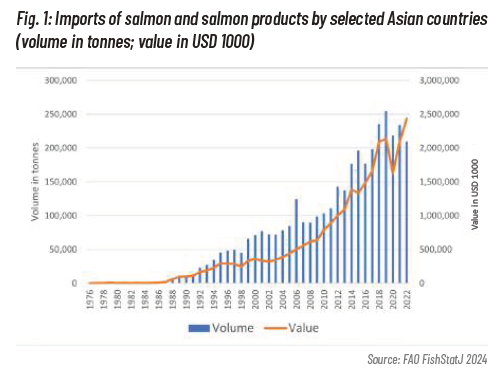

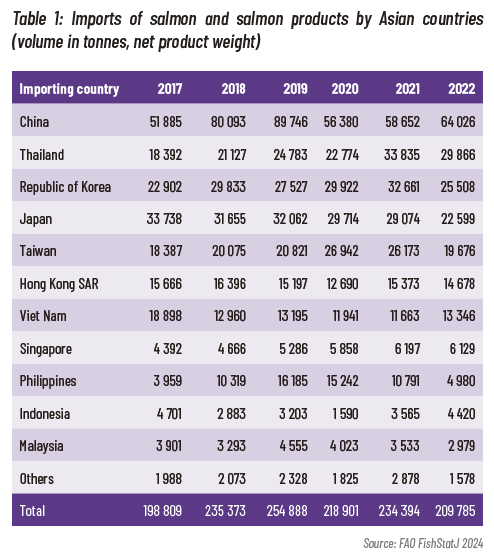

Nevertheless, all told, salmon has not been an important species on Asian markets until more recently, its consumption and imports in the Asian Far East and Southeast Asia having grown remarkably since the early 1990s. By 2022, it was estimated that imports of salmon to the most important Asian markets amounted to about 210 000 tonnes, net product weight (see Figure 1 and Table 1).

So, what happened?

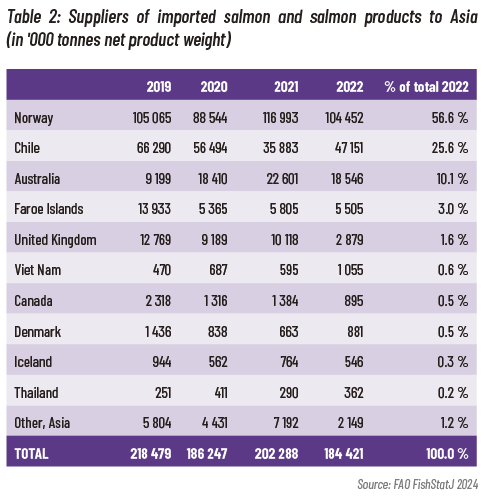

It was the advent of farmed Atlantic salmon, first introduced by Norwegian exporters, that stimulated Asian imports of salmon. Two other countries also stand out as suppliers to the Asian market: Chile and Australia. Chile is the second largest producer of farmed salmon, while Australia, which produces mainly Atlantic salmon, is benefitting from its geographical proximity to the Asian market. Chile in 2022 accounted for 25 percent of Asian imports, while Australia accounted for 10 percent.

Supplies are likely to increase further, and in the meantime, several Asian countries (including China and the Republic of Korea) are now trying to develop their own salmon producing industries. While this may mean increased competition for exporters like Norway and Chile, it is likely that the domestic production of Asian countries will supplement the existing supplies and help expand the market further. In the years to come, salmon will continue to play an important part in Asian seafood markets.

In recent years, Asian imports of salmon have fluctuated between 200 000 and 255 000 tonnes per year. Today, the major importers of salmon in Asia are China, Thailand and the Republic of Korea.

The “kitchen door strategy”

A major player in this was the young chef Frank Næsheim, who moved to Singapore in the mid-1980s and set up the Scandinavian restaurant “Vikings” on Orchard Road together with another Norwegian chef. They also established a trading company in order to take care of imports from Norway, and called the company Snorre Food Pty Ltd. The restaurant was closed after some years, but the trading company blossomed, mainly thanks to the strategy they had developed.

Frank knew that salmon was relatively unknown among Asian chefs, so he invited a selection of Singapore chefs to courses on the use of salmon in Asian cuisine. He organised competitions, one result of which was the publication of the book “Norwegian salmon in Asia” in 1989.

In Chinese cuisine, using salmon for the raw fish dishes (yusheng) also became popular. Yusheng (or lo sahng as it is sometimes called in Singapore and Malaysia) is a raw fish salad usually served in connection with Chinese New Year. It consists of strips of raw fish mixed with vegetables and a variety of sauces. The original dish used raw mackerel, but due to temporary supply problems, salmon was later offered as an alternative, and today, salmon is actually the most-used species for this dish.

“Project Japan”

A large part of the credit goes to Norwegian exporters. When they started planning their promotion of salmon, they realised that going through Japanese importers would be a waste of time. The importers were conservative and regarded salmon as being the wrong colour, the wrong shape and the wrong smell for sashimi.

The alternative for the Norwegian exporters was to take the “kitchen door” route once again: enticing famous Japanese chefs to accept salmon as an alternative raw fish. It was not an easy task. They started their promotion campaign, named “Project Japan” in 1986, but did not really see any great results until about 1995. It took almost ten years to gain acceptance of salmon on the Japanese raw fish market. But when it was finally accepted, it became a resounding success, not only in Japan, but around the world where sashimi and sushi have become amazingly popular.

While countries like China, Japan and the Republic of Korea have been, and are the dominant markets for salmon in Asia, other countries are also set to develop as salmon markets. Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam are all countries where the market can be expanded, and they are being targeted by the Norwegians.

Singapore, where much of this trend started, is of course a limited market with a small population. But it is very much a trading hub and the other Southeast Asian countries are being influenced by traders in Singapore.

Imports in South Asia have been slower but may be set to develop. Norway is launching a campaign for Norwegian seafood in general in India. In 2024, Norway and India signed a trade agreement, whereby certain Norwegian products, among them seafood, would be granted zero import duty in India. The challenge in South Asia is pretty much the same as the one faced by countries in Southeast and Far East Asia thirty years ago: salmon is not part of their cuisine or culture. Therefore, salmon exporters are facing a major task educating the market.

The future

The short answer is yes. One of the main reasons is that the main supplier, Norway, seems to have reached its limits in other markets, particularly in Europe. As much as 70 percent of Norwegian salmon exports end up in the European Union, and the volume of exports to the EU has been stagnating in later years. Norway wants to increase production of salmon (the Government has indicated a production target of up to five million tonnes by 2050!), and it needs to develop new markets. Asia is the most likely focus.

Asian investors have now become interested in aquaculture of salmon in Asia itself. There are several big projects either in the planning stages or already in operation in China, the Republic of Korea and Singapore.

China seems to focus on two major technologies: offshore floating installations and land-based recirculation aquaculture systems (RAS). Korea seems to focus mainly on land-based RAS, as does Singapore. As salmon is a cold-water species, the warm waters of Singapore will have to be cooled down, and this will no doubt add cost to the operations.

In South Korea, a large industrial conglomerate is developing its landbased technology called hybrid flow-through technology (HFS) and expects to produce 20 000 tonnes (live weight equivalents) per year. Production was expected to start in 2024.

Some years ago, China built the first large offshore floating installations for Norwegian salmon farming giant SalMar, called the Ocean Farm One. By building this structure, the Chinese shipyard learned a great deal about offshore salmon farming, and they have now developed their own designs and technology and are in the process of going through trial production.

These Asian initiatives will result in a higher production closer to the market. This does not necessarily mean that foreign suppliers will be pushed out of the market, but it will bring keener competition on these markets. But the markets are growing, and as a result of the massive promotion, they will grow fast. The domestic production will be a supplement to the imported supplies. However, it must be expected that there will be some pressure on prices, which in turn will benefit the consumer and lead to greater demand.

Traditionally, salmon was an expensive fish available seasonally and only in limited regions. Salmon farming and logistics changed that. As salmon farming developed, the price of salmon fell, and became available yearround all over the world thanks to air transport.

A trend that may play an increasingly important part in the market, and not only the salmon market but in the market for everything, is e-commerce. China has in some ways been a leader in this, and the company Alibaba has already offered salmon through its online services. In addition to its online promotion, Alibaba has, through its retail chain Hema, started offering Norwegian salmon on a grand scale.

A key word in promoting salmon in Asia has been information, or knowledge about the product and how it can be used. Norway is bringing groups of journalists and chefs to Norway to visit salmon farms and to teach them how to prepare salmon dishes. The “kitchen door strategy” is still being used in countries other than where it originated, and it probably will be used in many more, for example in South Asia.