Article II 4/2024: ONE KEY TO ENDING IUU FISHING: HOLDING VESSEL OWNERS ACCOUNTABLE

IUU fishing is also a significant threat to people, especially residents of coastal communities, because IUU fishers raid the waters that lawabiding commercial fishers depend on for their livelihoods. As a result, the fishers who play by the rules end up casting their nets for scraps in areas depleted by IUU activity. This happens most commonly in places where people can least afford to lose income or their ready access to seafood; these are often the same locales where governments lack the resources they need to adequately patrol their countries’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs), which extend 200 nautical miles from each country’s coast.

One of the major problems in stopping IUU fishing is the difficulty authorities face in knowing who ultimately profits from the illicit activity.

This issue extends throughout the commercial fishing industry, including those vessels that operate fully within the law. The true financial beneficiaries of fishing—referred to as ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs)—own the vessels and reap most of the financial gain but can be very hard to locate for several reasons. They sometimes conceal their identity behind a tangled web of flags of convenience, shell companies, ever-shifting vessel names and hard-to-trace registrations; these are all legal maneuvers that are often exploited by fishers or UBOs who have something to hide.

In one of the more infamous cases of IUU fishing, the non-governmental advocacy group Sea Shephard pursued an IUU vessel named the Thunder. The pursuit started in the Southern Ocean, and when it ended off the west coast of Africa more than 110 days later in April 2015, the boat sank, destroying potential evidence. The captain then relied on the conservationists who had trailed him for three months to rescue him and his crew.

In the end, the captain and two of his crew were sentenced to three years in prison. Although the prison sentence was overturned on appeal, related entities were ordered to pay EUR 25 million, a rare legal victory in the global fight against IUU fishing, although probably not enough to dissuade the Thunder’s owner. Experts estimate that the owner reaped some USD 60 million in the nine years that the Thunder plundered toothfish (marketed and sold as Chilean sea bass) from the Southern Ocean and faced no legal case or indemnity for the pollution caused when the vessel sank.

A tangled, murky web

In theory, finding and prosecuting owners of IUU vessels shouldn’t be difficult. The ships are, after all, very large objects that are constructed, sold and deployed for very specific purposes. So it might appear easy for authorities to check paperwork and arrest vessel owners when crimes are suspected.

But it’s much more complicated than that. For one, the vessel owner behind the illegal activities is rarely present when they occur, making it difficult to find evidence linking the owner directly to the crime. And the crimes themselves are often committed in one country’s waters with a vessel flagged to another country, or owned by someone in a third country, and often under the control of a captain hailing from yet another nation. This alone makes policing and legal proceedings challenging at best.

What’s more, all fishing vessels have a registered owner and a beneficial owner, and sometimes they aren’t the same person or entity. In fact, in the world of IUU fishing, the registered owner could be a shell company or other decoy. Further, some countries maintain “closed” vessel registries, meaning owners can’t register boats there unless they have clear ties to the country. To evade this prohibition, they often set up a shell or front company, registered to a local, to circumvent what is meant to be a protective effort.

In addition to the legal maneuvers that UBOs use to hide their identity, the true owner can also be difficult to determine because no international rules or requirements ensure full transparency. This is especially true for vessels that fish in areas beyond the national jurisdiction of their home country, which is increasingly the case as growing pressure on fish stocks is driving many vessels farther out to sea to bring in catch and profits. Oversight in these distant high-seas areas is even patchier than in the most underresourced nation’s waters.

And even when someone is held accountable for IUU fishing, it is typically one or more members of the crew, not those who orchestrate, organise and profit from the illegal activity. Because ownership is often obfuscated and regulatory structures are weak, the owners escape sanctions and fines. This is analogous to police arresting drug users and smalltime dealers on the streets while the cartels behind the drug trafficking go unpunished.

With ocean health and global fisheries straining under increasing pressure from overfishing, climate change and other challenges, ensuring that all fishing activity is sustainable, transparent and operating with effective oversight, including holding illegal operators accountable, is more important than ever. To that end, flag States to which vessels are registered; port States that accept the catch; coastal States and regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs); and other stakeholders must all do their part to clarify the true ownership of vessels. They also need to establish an internationally agreed-upon definition of ultimate beneficial ownership, strong company data collection mechanisms, and appropriate penalties for those who benefit most from IUU fishing.

There is no international consensus regarding who or what qualifies as a UBO. According to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)—an intergovernmental watchdog group that sets standards for nations and financial institutions to counter money laundering and the financing of terrorism—a UBO should always be a human being, rather than a company, and the threshold for ownership or control should be no higher than 25% of said company. But not all countries use this definition. Some set a higher threshold—as much as 50% of ownership or control. This lack of standardisation makes coordination difficult, especially at the RFMO level where Member States may have different definitions of a beneficial owner.

Financial transparency watchdog groups, such as the FATF and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), strongly recommend that countries develop a mechanism for obtaining documentation on beneficial owners, particularly the UBO, either through the banking system’s due diligence process or by mandating that corporations keep and promptly provide the ownership information upon the government’s request.

Alternatively, FATF recommends that countries collect UBO information in a national-level registry, similar to how fishing vessels are supposed to be registered at the country and RFMO levels. As of 2022, 97 countries have some sort of UBO registry. But these registries vary in their levels of transparency, how they define UBOs, and whether they allow corporations to be listed as the UBO or require that the UBOs be listed as individuals.

For example, in November 2022, the European Court of Justice cited privacy concerns in invalidating public access to UBO registries in the European Union. Although the current registry system has its flaws, rolling back public access would hinder efforts by watchdog and other civil society groups to locate and track beneficial owners and ensure that companies are complying with local and global rules.

Knowing a fishing vessel’s UBO can help enforcement officials shine a light on an issue that can be difficult to detect and ultimately prosecute. In some cases, countries maintain distant-water fishing fleets that work as teams to carry out IUU fishing, with some bad actors hiding within larger groups of vessels, making it very difficult for authorities to track and verify all fishing activity. And because modern fleets can freeze fish immediately, transfer catch to carrier ships and refuel from bunker vessels in the middle of the ocean, many can stay at sea for months, compounding the damage they do to fish populations and the ecosystem. This activity, known as transshipment of catch—when one vessel offloads its catch at sea to another vessel—can often hide illegal transfers.

Often, IUU fishers hover near the outer boundaries of EEZs—for example, off the coast of West Africa or South America, where this type of behaviour is so common that it is called the 201-mile marker. In such cases, vessels loiter close to the 200-mile EEZ line and often cross it to fish illegally before quickly retreating into international waters to avoid prosecution. IUU fishers frequently do the same around marine protected areas and other sanctuaries, darting in to steal fish at opportune moments but spending most of their time outside the boundaries.

Moreover, many IUU fishers are committing crimes beyond stealing fish. As detailed in a 2023 report by Earth League International and the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, international syndicates use IUU vessels to carry out a wide range of crimes, including human trafficking, drug and wildlife smuggling, money laundering and more.

For example, the report documents a phenomenon called “crime convergence” in which a syndicate that operated in China, Peru and South Africa smuggled shark fins, rhinoceros horns, Galapagos turtles, jaguar fangs and more to various countries in Asia. Aside from IUU fishing, the syndicate also was reported to have engaged in corruption, money laundering and human smuggling.

Labour abuse is an issue even among otherwise law-abiding vessels, but it’s far worse on IUU ships. Cases abound of forced labour on illegal fishing boats, with documented incidents of captains using children as crew and keeping workers at sea for months or years at a time in hazardous and inhumane working conditions. In an infamous case, an IUU captain kept some of his crew in cages on an island to guard against them escaping when the ship wasn’t at sea.

Similarly, the Indonesian crew of a notorious IUU vessel, the STS-50, toiled at sea for months without pay as the captain maneuvered to evade authorities. Fortunately, Indonesian authorities intercepted the boat in 2018 after an odyssey during which authorities from numerous countries tracked the ship virtually. But even though the crew was released, the vessel seized and the captain detained, the trail on the UBO went cold. Analysts at Interpol estimated that the boat had poached upwards of USD 50 million worth of toothfish over the years, and whomever profited from that, faced no punishment.

The solution to this problem of corporate transparency in fisheries isn’t complicated, but will take cooperation and coordination among multiple players. First, all governments should maintain UBO registries and share that information with fisheries ministries and maritime law enforcement officials of their own and other countries. When a motor vehicle or aircraft is used in a suspected crime, authorities can quickly act to make public not only the name of the owner of the vehicle but also his or her likely whereabouts; the same should happen in suspected IUU cases.

Next, flag States already have a responsibility to ensure that vessels flagged to them obey the laws of the waters in which they fish. These States should do a better job of enforcing that policy, monitoring activity and adding a mandate that no boat gets a flag State authorization without full clarity on who owns the vessel and profits from its operation. More precisely, flag States should collect UBO information when flagging vessels, or when issuing a fishing license or signing a fishing agreement. They can use Taiwan as a guide: there, companies that plan to fish in foreign waters must register with, and gain approval from, the government before they begin fishing in another country’s EEZ. Failure to comply with this mandate can result in financial penalties.

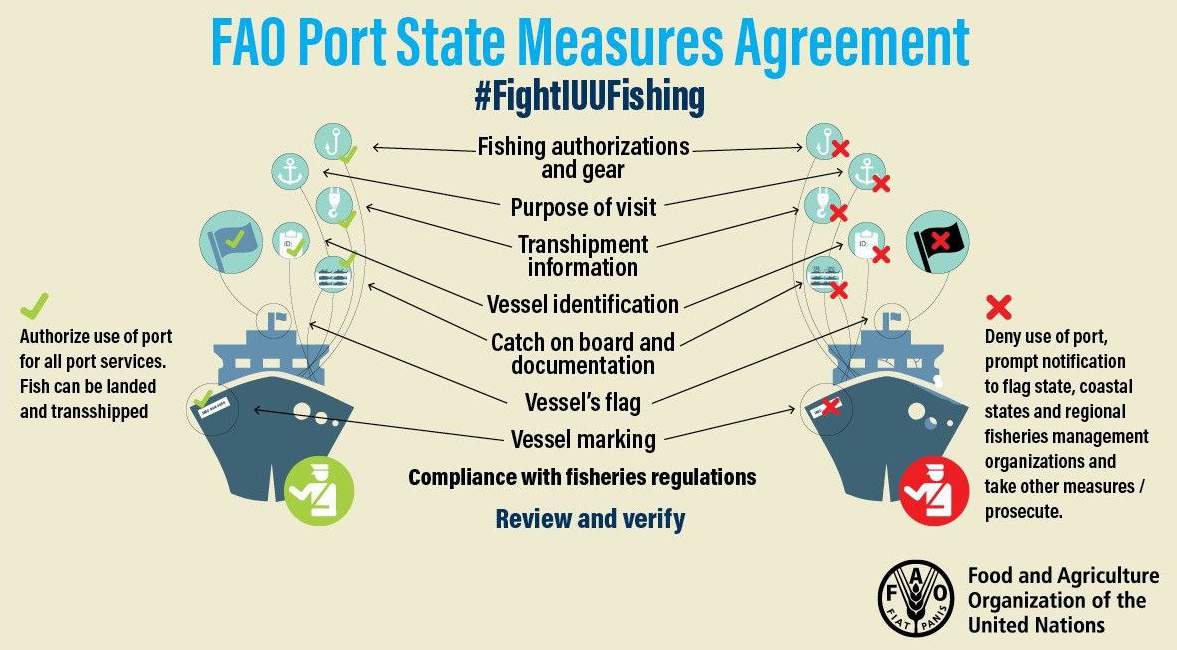

Coastal States should also join and implement the Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA), a treaty adopted by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in 2009. The PSMA entered into force in 2016 and is now legally binding in over 100 States, all of which are legally bound to strengthen port controls for foreign-flagged vessels offloading catch. The agreement aims to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing by strengthening and harmonising port controls around the world, thus making it much harder for IUU fishers to search for an amenable port when seeking to offload catch.

The PSMA’s success hinges on port officials, both within and among States, sharing information. Fortunately, FAO created two tools to do precisely that: The Global Information Exchange System (GIES) and the Global Record of Fishing Vessels, Refrigerated Transport Vessels and Supply Vessels (Global Record). According to FAO, the GIES is the first global system for exchanging compliance information and “permits the sharing of vital information between port, flag and coastal States, as well as other relevant organisations.”

Although the Global Record is not directly linked to the PSMA, FAO maintains it as a collaborative initiative to certify data and information about fishing vessels and their activities, specifically to help fight IUU through greater transparency and traceability. The organisation does not currently mandate that UBO information be entered into this database but is beginning to explore how to do so.

Lastly, governments should penalise citizens engaged in IUU fishing— even in foreign waters—especially the UBOs and others who reap the bulk of the profits from the illegal activity. Given the amount of money UBOs make from illicit fishing and the damage the activity causes to the environment and other people, governments should pursue significant fines and potentially prison terms for those found culpable, instead of “slap-on-the-wrist” punishments that do little to dissuade further crimes. An example of such a regulation is the European Council Regulation 1005/2008, which the European Union implemented to curb such behavior, although it hasn’t yet been used much by its Member States.

Encouragingly, signs of progress are emerging. In January, a United Nations Joint Working Group—comprising Member States from FAO, the International Maritime Organization and the International Labour Organization—met in Geneva in January 2024, where delegates agreed to hold an expert roundtable on collecting beneficial ownership data for the Global Record, which would be essential to stop those orchestrating the systematic plunder of the ocean.

Conclusion