Article II 4/2024: EQUITY AND SUSTAINABILITY IN TRANSBOUNDARY

TUNA FISHERIES

A narrowly focused short-term view of national interest will jeopardise such cooperation. All parties must look towards long-term, shared interests and explore collective and innovative solutions that avoid a disproportionate burden on developing States and minimise disruption, while ensuring long-term sustainability. The international legal framework, and global commitments toward sustainable development, require that sustainability and equity be considered together.

This article discusses the international legal framework for transboundary fisheries, sustainable development commitments, and the need to find new equitable pathways to sustainability. An inequitable conservation and management measure contradicts international commitments, and is unsustainable in practice, while unsustainable exploitation similarly contradicts international commitments and is inequitable for current and future generations.

Ocean governance

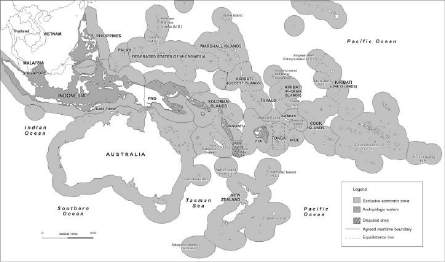

The Law of the Sea applied a zone-based order, dividing the oceans into areas within and beyond national jurisdiction, each zone being characterised by a different set of rights and responsibilities. In internal waters and territorial seas out to 12 nautical miles, coastal States hold sole jurisdiction to authorise and undertake activities, free of external interference within internationally agreed limits.5

2 Tommy T. B. Koh, “Constitution for the Oceans” in United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary ed. Myron H. Nordquist, (Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1985).

3 Philippe Sands, Lawless World: America and the Making and Breaking of Global Rules (London, United Kingdom: Penguin, 2005).

4 As of 7th September 2023; United Nations, United Nations Treaty Collection – Chapter XXI Law of the Sea, 7 September 2023, https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetailsIII.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXI- 6&chapter=21&Temp=mtdsg3&clang=_en

5 Articles 2, 19, 21, 49, 52 of UNCLOS

6 Article 56(1)(b)(i-iii) of UNCLOS

7 Art 56 of UNCLOS: “In the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State has: (a) sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds […]”

Beyond 200 nautical miles are the high seas, which are considered to be a global commons and cannot be claimed by any State. The Law of the Sea recognises the “freedom of the sea” for the high seas,8 subject to conditions, including the requirement that States cooperate with each other, conserve and manage marine living resources, and protect and preserve the marine environment.9

In the early 1990s, it became increasingly apparent that the Law of the Sea was insufficient to address increasing threats posed by overfishing, overcapacity, and destructive fishing practices.10 Subsequently, the global community negotiated new initiatives to strengthen the global framework for fisheries management, including the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) 11, and the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries 12.

UNFSA is the most significant of these supplementary agreements regarding straddling and highly migratory fisheries and is an implementation agreement of the Law of the Sea. It institutionalises the duty to cooperate and explicitly requires all UNFSA parties to apply all conservation and management measures established by existing Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs). It also limits access to these fisheries to parties that participate in RFMOs, or at the very least, agree to implement the relevant RFMO’s measures.

UNFSA is often cited for modernising fisheries management and strengthening the duty to cooperate. But it also includes important provisions that recognise the special needs, rights and aspirations of developing States, particularly the need to avoid adverse impacts on, and ensure access to fisheries by, subsistence, small-scale and artisanal fishers, women fishworkers, and Indigenous Peoples. It also explicitly requires parties to ensure that conservation measures do not result in transferring, directly or indirectly, a disproportionate burden of conservation action onto developing States. It is important to note that this requirement only applies to developing States, as its scope has sometimes been confused during RFMO negotiations.

The FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries also similarly recognised development concerns, noting that the capacity of developing countries to implement fisheries management should be duly taken into account. Paragraph 5.2 of the Code of Conduct states: “In order to achieve the objectives of this Code and to support its effective implementation, countries, relevant international’ organizations, whether governmental or non-governmental, and financial institutions should give full recognition to the special circumstances and requirements of developing countries, including in particular the least-developed among them, and small island developing countries. States, relevant intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations and financial institutions should work for the adoption of measures to address the needs of developing countries, especially in the areas of financial and technical assistance, technology transfer, training and scientific cooperation and in enhancing their ability to develop their own fisheries as well as to participate in high seas fisheries, including access to such fisheries.”

8 Part VII of UNCLOS

9 Articles 117, 118, 119, 192 of UNCLOS

10 Rosemary Rayfuse, “The Interrelationship Between the Global Instruments of International Fisheries Law” in Developments in International Law, ed. Ellen Hey, 107-158, (Netherlands: Kluwer Law International, 1999).

11 UNFSA, Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea 10 December 1982, Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks. (New York, USA. International Legal Materials, vol. 34. 1995).

12FAO. Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. 1995. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/ bitstreams/4a456053-db08-4362-875a-2fdc723c1346/content

• Reducing pollution

• Restoring ecosystems

• Minimising ocean acidification

• Ending overfishing

• Conserving coastal and marine areas

• Reforming fisheries subsidies

• Increasing benefits to Small Island Developing States

Sustainable development

The sovereign rights create immediate and long-term value for the coastal States, both financially and in other terms (e.g. food security, livelihoods, etc). Fishing licenses and access agreements are mechanisms through which governments earn revenue and manage activity. The access fees are calculated, in part, based on the likely catch in the specified period of the access agreement, and the value of that catch, informed by historical and current data. A recent study determined that access arrangements pay for access – not future rights or catch history13 - and highlighted the importance of accurate reporting and catch attribution for sustainable development.

13 Andriamahefazafy, M., Haas, B., Campling, L., Le Manach, F., Goodman, C., Adams, T. and Hanich, Q. Advancing tuna catch allocation negotiations: an analysis of sovereign rights and fisheries access arrangements. npj Ocean Sustain 3, 16 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-024-00055-9

RFMOs have mandates to consider the best available science and adopt appropriate conservation and management measures. For both the IOTC and WCPFC, conservation measures must be compatible across both EEZs and high seas and apply across the range of the stock. Therefore, negotiations over potential proposals must consider the impact of each proposal on the interests of diverse coastal and fishing State members, and ensure that the chosen approach achieves sustainability objectives while avoiding a disproportionate burden on developing States. This is not to say that RFMOs must avoid applying any conservation burden onto developing States, but that it must not be disproportionate.

This is often a difficult challenge, particularly when data is limited, or in circumstances where developing States have not had the opportunity to develop their own fisheries aspirations. For example, applying a conservation limit for an overfished stock that is primarily based on historical catch may inadvertently lock out developing States that have not had fishing opportunities, while rewarding flag States with vessels that overfished the stock. Such an outcome would contradict international equity commitments noted previously, and might also be considered to contradict the “polluter pays principle”, rewarding the polluting (overfishing) activity.14

Within the IOTC, members can opt out of measures that they oppose. These opt-out procedures have been commonly used and have limited the effectiveness of conservation and management measures, with six members currently having opted out of the current yellowfin tuna measure.15 While this might address equity concerns, it directly undermines sustainability goals and prevents the rebuilding of a key stock.

The WCPFC does not allow for opt-outs, but has adopted measures that ensure that the Commission must explicitly consider the special requirements of developing States and avoid a disproportionate burden.16 For example, the WCPFC conservation and management measure for tropical tuna includes measures that exempt small island developing States from some provisions so as to avoid a disproportionate burden.17 While such exemptions are important to address equity concerns, they undermine the integrity of conservation and management measures and may inadvertently create further equity concerns for other members.18

Balancing interests

Both the IOTC and WCPFC need to consider future strategies to transparently address equity concerns while achieving sustainability goals. Both organisations have initiated allocation processes that could meaningfully implement these goals and balance diverse interests, but both are struggling to negotiate an agreement. Meanwhile, climate change is accelerating and likely to further exacerbate equity concerns as it impacts on the productivity and distribution of fish stocks.19

RFMOs generally apply a consensus-based decision-making approach, even when they have the option to vote. While the consensus-focused approach is often criticised for resulting in weak outcomes, consensus is important as decisions can only be implemented through domestic jurisdictions; as flag States, coastal States, port States and market States. If a State objects to a proposed measure, or does not have the capacity to implement it, then that State is unlikely to comply.20

Win-win solutions are needed that recognise the sovereign rights of coastal States, and allow for innovative compatible management across EEZs and high seas. This requires creative negotiations that explore package deals that provide benefits for all, capacity-building programs and funding that ensure all parties can effectively participate and implement any decision; and allocations that enable development aspirations, minimise disruption, and ensure long-term sustainability goals.

14 Kok-Chor Tan , “Climate reparations: Why the polluter pays principle is neither unfair nor unreasonable,” WIREs Climate Change 14 (2023):e827.

15 Resolution 21/01 on an interim plan for rebuilding the Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna stock in the IOTC area of competence

16 CMM 2013-06 on the criteria for the consideration of conservation and management proposals.

17 CMM 2023001 for Bigeye, Yellowfin and Skipjack Tuna in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean

18 Bianca Haas, Kamal Azmi and Quentin Hanich, “The unintended consequences of exemptions in conservation and management measures for fisheries management,” Ocean & Coastal Management 237 (2023): 106544.

19 Johann D. Bell et al., “Pathways to sustaining tuna-dependent Pacific Island economies during climate change,” nature sustainability, 4 (2021): 900-910.

20 Quentin Hanich, Feleti Teo and Martin Tsamenyi, “A collective approach to Pacific islands fisheries management: Moving beyond regional agreements,” Marine Policy 34 (2010): 85-91.

Conclusion

The sustainability of transboundary fish stocks, such as tuna, depends on more than just science-based decision-making. It fundamentally depends on effective cooperation between sovereign States and their subsequent implementation of conservation and management decisions. This requires that all parties have the capacity and agency to determine their own national interest, and participate effectively in a negotiation.

Cooperation must consider history and context when negotiating conservation and management proposals. International relations occur within a geo-political, institutional, economic and trade context that has been formed by centuries of colonialism, capitalism and power disparities. Ignoring this does not make it go away. Failure to consider this history and context ignores ongoing inequities, marginalises development aspirations, undermines legitimacy, deters participation and subsequent implementation, and contradicts international development commitments.