Article II 3/2025 - DEEP SEA MINING THREATENS OCEAN HEALTH AND FISHERIES

But a growing body of science suggests that optimism is misplaced, and that mining could threaten not only biodiversity but also industries reliant on living marine resources, such as fishing. A study published in the journal Nature in July 2023 found high potential for climate disruption to drive numerous species of commercially fished tuna into an area of the Pacific Ocean where extensive mining is being planned. Mining this area could lead to adverse effects on marine life and economic harm. Sediment plumes and other related consequences from mining potentially risk disrupting tuna feeding and reproduction patterns and might increase the population’s exposure to toxic metals which accumulate and make their way to consumers. The authors found that sediment plumes from mining could also reduce visibility and increase tunas’ stress hormone levels.

Other challenges raised by seabed mining include noise and artificial light, which can interrupt communication, navigation and other behaviour patterns among marine life within a naturally dark and silent environment. There’s also the fact that some deep sea species – such as the Greenland shark and many types of coral – live extremely long lives by human standards and take decades to reach reproductive age, which means that they are vulnerable to being severely endangered or wiped out entirely by sustained mining activity.

In response, the Global Tuna Alliance and other seafood industry groups have joined some governments and major companies in calling for a moratorium or precautionary pause on deep sea exploitation activity.

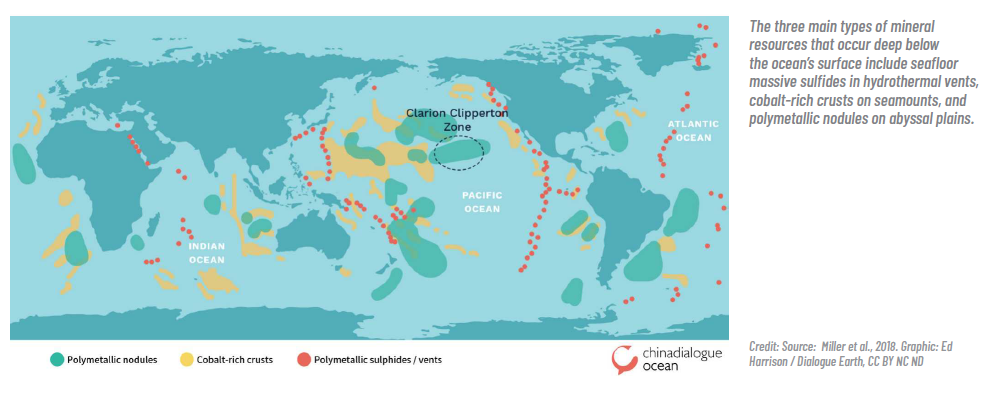

Experts say that all manner of deep sea ecosystems being targeted for seabed mining could take centuries to recover from significant damage – if they’re able to rebound at all. The three main types of mineral resources (see map on the next page) include seafloor massive sulfides found in hydrothermal vents, which are essentially underwater hot springs where volcanic magma swells into the freezing depths of the ocean; cobalt-rich crusts occurring on underwater mountains, known as seamounts, that rise hundreds or thousands of feet from the seafloor; and polymetallic nodules, potato-sized formations that contain manganese, nickel, copper and cobalt and are concentrated on the abyssal plains, which are large, flat expanses covering the deep ocean floor.

It’s these nodules that mining companies and governments are currently seeking. The nodules took millions of years to form, and it’s unclear how removing them en masse would affect the ecosystem. Even as miners advance their plans, there are no rules in place to protect the marine environment, which is one of the obligations of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an entity created under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to govern deep sea mining in international waters.

There’s also a lack of information on the risks mining could pose to fisheries. For example, scientists have very little understanding of how mining might affect the water column where fish live. And perhaps most glaring, the ISA has not included the fishing sector as an active stakeholder in negotiations on mining regulations. This must change.

How we got here

As a push to allow deep-seabed mining increased, the ISA in 2016 began facilitating multilateral negotiations to develop a regulatory framework for the activity and in 2019 published draft regulations. But almost a decade later, ISA Member States have been unable to finalize those regulations. This is because fundamental aspects of the regulatory regime remain incomplete, and as The Pew Charitable Trusts and other groups have pointed out, the draft rules have at least 30 major outstanding policy issues. These include a lack of consensus on how to assess the effects of mining, what amount of environmental harm can be allowed, and how to enforce the regulations once they are in place. Additionally, ISA Member States have not yet fully considered a range of additional subsidiary rules that are mandated to be adopted with the main regulations and would cover topics such as how to consult countries and other stakeholders, like the fishing industry, that could be affected by mining – a docket that will likely require extensive debate and may take several years to complete.

When the regulatory framework is finalized, it must still be implemented effectively. Currently, the ISA functions as an international organization focused on seabed exploration and prospecting as well as facilitating multilateral negotiations on how to govern mineral resources. It is not equipped to simultaneously act as licensor, regulator, and royalty receiver and distributor. Those responsibilities are typically performed in national settings by highly specialized bodies. And the complexities of mining occurring hundreds of kilometres offshore and thousands of metres below the surface of the sea would make it more dificult to regulate, monitor and enforce than typical marine activities.

A push to allow mining

The ecology of the deep ocean is particularly sensitive to damage and slow to recover. Tracks from mining trials 30 years ago are still visible today, with researchers finding reduced microbial activity in these areas, which has implications throughout the marine food web. And larger forms of deep sea marine life directly depend on the nodules being targeted, so any damage caused by removing them would negatively affect the integrity of the food web and be permanent. Yet, companies could begin mining before ISA Member States agree on a final set of regulations.

For example, one mining company is seeking to start operations by 2026 and has indicated its intention to pursue options such as applying for a permit through a government that has not ratified UNCLOS, or submitting an application to the ISA under a clause that could allow for unregulated mining. This latter possibility exists because of a nuance in the ISA’s charter that requires it to adopt regulations within two years of receiving notification that an application is forthcoming. If the ISA fails to meet that deadline, it must still consider the subsequent application.

In July 2021, the company notified the ISA of its intent to apply through a sponsoring Member State. The ISA missed the July 2023 deadline to adopt the regulations and now faces the possibility of granting that mining application without having regulations in place.

The case for a precautionary approach

Given how fast mineral needs change and the fact that recycling is improving, many experts question if there is suficient long-term need for deep-seabed minerals to justify the risks of mining. For example, companies have developed lithium batteries and a newer sodium-based battery technology that do not rely on materials sourced from the deep sea. In fact, one-third of electric vehicles produced today do not use the metals that seabed mining could supply.

Another reason for a moratorium or pause on mining activity is that even in the most well-studied regions of the deep sea – including areas where governments and companies are exploring for minerals to mine – significant gaps persist in experts’ understanding of the environment and the species it supports. Scientists estimate that more than 5 000 benthic species – organisms that live on the seafloor – in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, which is located in the Pacific between Mexico and Hawaii and is the world’s largest deep sea mineral exploration frontier, remain unnamed and thousands more remain undiscovered.

Although scientists generally understand many of the likely effects of deep sea mining, in the absence of suficient information, it is impossible to ascertain with any confidence how intense, far-ranging, or long-lasting any environmental harm will be. This, in turn, prevents ISA Member States from setting appropriate thresholds for damage that would avoid harm to the marine environment.

ISA Member States continue to debate the contentious issue of what constitutes a fair and suficient payment rate and have not begun meaningful discussions on how to ensure equitable, transparent payments to countries.

Meanwhile, over the past three years, there have been growing calls for a moratorium or precautionary pause on seabed mining by more than 30 countries, along with indigenous groups, scientists, conservation organizations and others concerned about insuficient scientific knowledge of the deep sea. Many have cited the need for robust regulations and more confidence in the ISA as an effective regulator.

And an increasing number of investors, insurers and reinsurers, and downstream mineral users such as private companies have expressed significant concerns about deep sea mining, threatening the viability of any potential seabed mining industry.

Downstream users that have joined the call for a moratorium include technology companies and automotive manufacturers that specifically cite environmental concerns.

Relationship to other international agreements

Outside of the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, there is significant geographical overlap between prospective mining areas and fishery stocks such as tuna, billfish and squid throughout the global ocean. And the effects of deep sea mining could extend beyond the boundaries of these areas, which underscores the importance of understanding the risks and examining how countries’ fishery catches might be impacted by mining.

Conclusion

For the foreseeable future, the best course of action is for ISA Member States to implement a moratorium or precautionary pause on mining and work to thoughtfully address scientific gaps so that decisions can be fully informed and stakeholders – including those reliant on healthy fish stocks – can be confident in the future of the ocean.